And besides, I thought, it’s probably good for me to figure out what preparing for disaster would look like anyway since I literally never had done that before. And while we’re on that note, somewhere in the midst of my frenzied pre-evacuation watch prep, I had the thought: What’s the use of being an anxious person if I’m not going to be prepared in an emergency? If you tend to be an anxious person, your thoughts often reside somewhere in the future--consciously or subconsciously worrying about something that is not currently happening. Even though my anxiety often shows up as sensations in my body without a clear cognitive trigger, it's still fair to say that in general I’m a bit of a worrier and a planner. Some of this planning is useful; some of it is gratuitous; and some of it is annoying (sometimes to others and occasionally to me). Much of it is unnecessary even if benign. But here, in a situation where anxious planning would have finally come in handy, where there is actually some logic and wisdom to prepping for a situation you’re not currently in, I was woefully ill-prepared. As in, I was 100% not prepared to evacuate. I tried not to waste time wondering why and how an anxious, planner-type person like myself could possibly be so unprepared for an emergency. First of all, I did not have time to waste on this because did I mention I was preparing for an emergency?!??! Second, I already knew why. When it comes to really scary things that probably won’t, but definitely might happen (like an earthquake) or really scary things that definitely will happen, but we don’t know when (like death), I seem to switch from planner to avoider. Situations for which my planning would come in super handy (e.g., preparing earthquake prep kits and advanced directives), that’s when I avoid it like some, but not all of us avoid getting the coronavirus. My hypothesis is that certain realities are so overwhelming or scary, that when I think about preparing for them, something in me shuts that shit down.

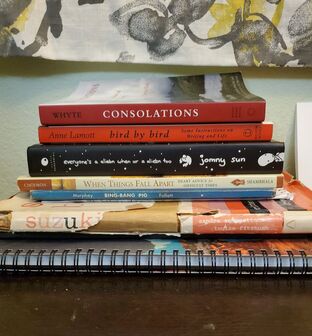

So there I was, suddenly preparing for something scary and overwhelming, that I literally never dreamed I would be dealing with. Jewish girls from Brooklyn don’t tend to have wildfire evacuation prep in their vision of the future. And even living in Portland for twenty years, this was the first time it was even a remote possibility. (Thanks, climate change.) Everything felt hectic and stressful and exhausting, but I just kept doing what I could when I could. Even as I was prepping, I didn’t think it was likely we’d have to leave. I just wanted to be totally ready just in case. Since we weren’t even in the green zone yet, I focused first on necessities: food, first aid kits, flashlights, batteries, hand crank radio, clothing, toiletries, cat supplies, important documents. Each evacuation list varied a bit, but they all said to make sure to grab family heirlooms, photographs, cherished art, or anything else that is “irreplaceable” and holds sentimental value. This is where I was stumped. I avoided it for a couple of days. I started to look around my house and consider what I would take and what I would leave behind. What pictures would I bring? All of them? None of them? So much is digital, but what about the hundreds of photos I have from before digital cameras existed? And art? Cards? Yearbooks? Journals? When faced with what would I bring, the simplest and only answer I could come up with at first was nothing. It was too hard to decide. I couldn’t even imagine where to begin. I started thinking about how strange and sad (but also liberating?) it was to consider I might not bring any of it with me. That the house and everything in it might burn down and I would be left only with my diminishing memory (and many thousands of pictures safely residing in the cloud). What does it mean if I’m willing to leave all of this behind? How will I feel about these items that I was ready to throw in the fire (or at least not rescue from it) if we get to stay? Will they not matter anymore? Will they feel betrayed? Will I feel guilty? As more time went by and the essentials were properly packed and lined up in the garage in case we ever found ourselves needing to GO NOW, I allowed myself to revisit the possibility of bringing non-essential, sentimental items. I let my eyes wander through bookshelves and gently shuffle through drawers, not in a particularly thorough or methodical way, but enough to give things a chance to jump out at me (or not). This time around, certain items began to inch their way toward me. A book or two or three slid themselves out from the shelf into my hands. Soon they were joined by a stack of hand-written letters; a few journals; a handful of photos from my first apartment with my husband twenty-two years ago when we were babies playing house in Mighican; a playbill from a show that took me six years to work up the courage to participate in and was a highlight of my life; my wedding album. The books I grabbed are all replaceable, except maybe one that might be out of print. It seemed silly to take any of them along. But this thought came to me that changed my approach: What if you’re not only thinking about what you want to save, but what you would be so grateful to have if you lost everything? If all of your belongings and your home were taken by fire, and you and your husband and your cats had safely evacuated; if you were feeling simultaneously devastated by all you’d lost and so thankful to be alive and with your family; what would you thank your past self for grabbing at the last minute? In this moment, my avoider self handed the reins over to my planner self. For just a few moments, I let myself imagine the unthinkable. I’m in my car having just learned that my neighborhood was hit by the fire, and my house and everything in it was gone. Tears stream down my face staining the puppy photos of the dog who’s been gone for seven years, but was with us for fourteen; arms tightly wrap around our wedding album; shaky fingers glide over the pages of the journal I kept when I was twenty-five and heartbroken; eyes desperately drink in the medicinal words of Pema Chodron’s When Things Fall Apart, or the sweet nostalgia of childhood favorite Suzuki Beane. Once I was willing to put myself in the very place I spent so long avoiding. I was able to think about that future self with tenderness, and offer her some gifts. I imagined her thinking about how loving of a gesture it was for me to pack these particular items away for her, how she would feel seen and loved, and cared for. How she would treasure having just a few cherished items to hold on to as she faced rebuilding her life. I saw her in a new home finding special places for these salvaged treasures, and how she would feel the way they connected her to her past. Once the evacuation risk seemed to be behind us, I started to slowly unpack; to think about what I learned and how I’ll be so much more prepared next time; to feel gratitude for this home I’m so sick of being mostly stuck in seven months into this pandemic. I had set aside a handful of books for my go bag, but they never made it in. I was just beginning to gather the sentimental items when the fire risk decreased, and so I never actually got as far as packing them away. Rather than returning them to the bookshelf, I took the pile of books I had set aside and left them on my writing desk where they had been waiting to be packed. I decided to leave them for a while.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

authorfara tucker (she/her) is a poet, copywriter,life cycle celebrant, former therapist, and current therapy client. archives

September 2022

categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed